- Durani Jawed Waziri, the former spokeswoman to former Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, escaped Kabul a year ago.

- She has resettled in the United States. But she thinks daily of Afghanistan and its government's collapse.

- "I never thought that one day we will lose everything," Waziri said.

ALEXANDRIA, Virginia — Afghanistan's presidential palace was strangely quiet. As Durani Jawed Waziri walked down the long hallway to her government office, she found herself alone.

One by one, she swung open her colleagues' doors. They were empty.

Panic gripped her. Her eyes swelled with tears.

It was the morning of August 15, 2021. By day's end, Taliban insurgents would celebrate inside the palace as they captured Kabul, the capital, and overthrew Afghanistan's elected government.

Waziri knew the Taliban had been mobilizing since President Joe Biden announced the withdrawal of US troops that spring. She had been receiving death threats for months as a high-ranking public official, recently promoted to be a top aide to Afghanistan's national security advisor after serving for three years as a spokeswoman to President Ashraf Ghani. Taliban forces killed one of her colleagues on August 6 – the same day they seized Zaranj, the first of many provincial capitals to fall. Intelligence officials kept warning Waziri to "be careful."

Still, going to work that Sunday, Waziri never imagined her country would crumble so quickly, so abruptly.

"I would leave Afghanistan in advance if I knew," Waziri said. "But no one knew."

A year has passed. Waziri was one of more than 85,000 Afghans who fled for the United States. But as she adjusts to life in Northern Virginia, Waziri is haunted by her government's collapse and the harrowing escape she had made from her home country.

"It was very difficult for me to believe it," the 36-year-old recounted thinking as she left the presidential palace for the last time and watched Kabul spiral into chaos. "Can you believe the whole city – the whole city – was running on the streets?"

The Taliban has since deepened divisions in Afghanistan and eroded human rights, mainly for women and girls. Sanctions have isolated the country from the rest of the world, destroying its economy and triggering widespread hunger. Tens of thousands of Afghans who had allied with the United States and promoted democracy remain stuck in a country now ruled with theocratic intolerance.

Waziri says the United States, which first struck the Taliban and Afghanistan-based al Qaeda militants in 2001 after the 9/11 attacks, only to wage a war of oscillating intensity there for the next 20 years, has a moral obligation to help the Afghan people. Their continued suffering serves as a reminder of work left undone.

"Afghanistan is the heart of Asia," Waziri said from her one-bedroom apartment just across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. "If there is peace, all this region will be in peace. But if it's like this, all the region will be sick."

As for Waziri, she aches for the day when she can return home and continue serving her country – even if she has no idea when that day will come.

Her escape

Chinar trees cover the presidential palace's grounds. In the winter, fresh snowfall coats their branches, illuminated by the morning sun. Waziri recalled gazing at their beauty through her car window as she rode to her office building, determined to improve her country.

She became President Ashraf Ghani's spokesperson in March 2018. Armed conflicts among ISIS-K, the Taliban, and US and Afghan forces had been escalating at the time. Then-US President Donald Trump had deployed more troops to the country.

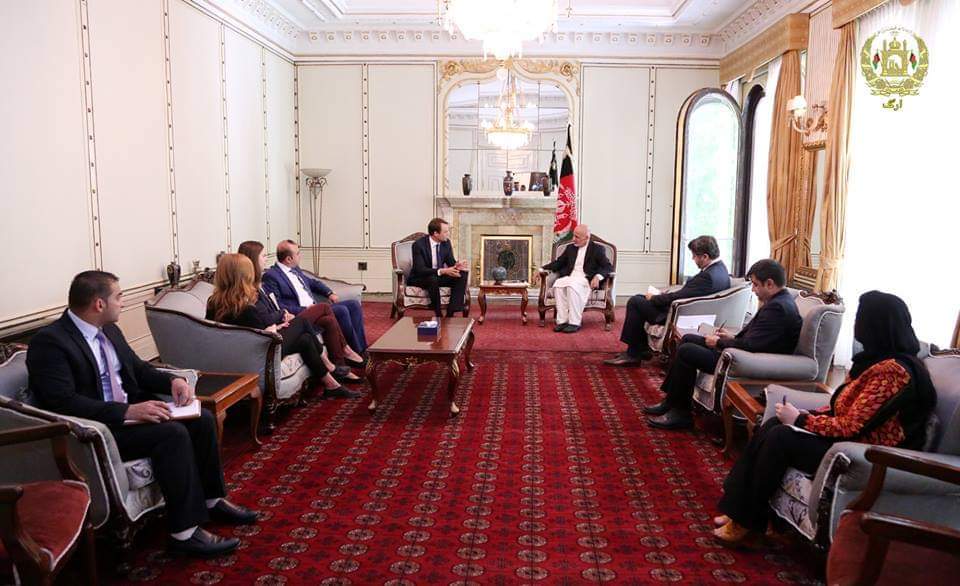

Waziri was responsible for ensuring that public messaging aligned with the president's politics. She drafted notes during Ghani's meetings, signed off on press releases, and traveled with him across the country. Work days frequently extended late into evenings. The high-profile role, particularly as a woman, put a target on her back.

"All people will not like you," she said.

Though Waziri wasn't intimidated. An attorney by training, she had grown used to working in high-pressure, male-dominated environments. Her decade-long career featured stints in law firms, Afghanistan's Ministry of Justice, and the US-based embassy. She studied Islamic law at Kabul University and received her master's of law on a scholarship at Ohio Northern University. Under Ghani's administration, Waziri championed rule of law, good governance, and women's rights – values she believed would better a country plagued by corruption.

"I was very hopeful for Afghanistan," she told me. "I never thought that one day we will lose everything."

But that day came on August 15. Fearing for her life, Waziri refused to sleep at her house once the Taliban sacked Kabul, seized governmental phone lists, and cut off her line. She stayed with her in-laws as she planned her getaway. There was no opportunity, nor time, for goodbyes with colleagues, friends, family members.

On August 18, Waziri, her husband, and 16-year-old stepson left for Kabul International Airport with one purse, two duffle bags and a 15-pound carry-on with their utmost essentials – her university degrees, a couple of outfits. They joined thousands of Afghans in a desperate scramble to flee the country.

The mayhem forced Waziri and her family to leave the bulk of their belongings behind as they shoved through the crowd to board a US military aircraft out. Waziri took their passports and her wedding album in her purse, and nothing else.

American air bases in Qatar and Germany became Waziri's immediate places of refuge. She described awful living conditions there: the restroom line took three hours in Al Udeid, her daily meal consisted of one egg and one potato in Ramstein. After a week, she finally flew to the United States.

In those first few months, Waziri felt numb to her new reality, more than 7,000 miles away from home. The daily things that had brought her joy no longer did.

"I'm a very good cook. I like cooking," Waziri said. "I didn't want to go to the kitchen even. I didn't want to clean it. I had a different feeling. I was thinking that I'm in a hotel, maybe for a few days and a few nights, then I will be back, you know?"

A moral obligation

On Waziri's forearm, there is a tiny spatter of scars. They formed when an Afghan woman had recognized Waziri at the air base in Germany and dug her nails into Waziri's skin, claiming she was part of the reason Afghanistan collapsed.

To Waziri, every party is to blame for Afghanistan's unraveling.

Warlords, empowered by the US mission in Afghanistan, pocketed millions of dollars and soiled the government with corruption. Trump's February 2020 deal with the Taliban to withdraw US troops emboldened the extremist group. Biden, despite warnings from his own national security and military officials about the likelihood of a Taliban takeover, carried out his predecessor's plan. The trillion-dollar war, which the US started to oust the Taliban from power, ended with the Taliban ruling again.

"The Taliban didn't come to Kabul or took over Kabul by force," Waziri said. "It was us – that we failed in our governance."

Under its regime, hard-earned freedoms have vanished: the Taliban has banned secondary- and college-aged girls and women from attending school and restricted women's dress, travel, and work. Media and speech are suppressed. A few countries – including Russia, China, and Pakistan – have established some level of relations with the Taliban, but none have recognized it as Afghanistan's legitimate government. The international sanctions, coupled with the Taliban's policies, have left Afghanistan on the brink of universal poverty.

"What about the people of Afghanistan? What about those 40 million people of Afghanistan?" Waziri pressed.

Some money is still flowing into the country. The US has provided more than $770 million in humanitarian relief to Afghanistan during the past year, yet aid groups have stressed that emergency assistance alone won't fix the country's battered economy. Cash-flow shortages have disrupted the banking sector and prevented Afghans from earning salaries, paying for groceries, and returning to anything that resembles ordinary life. To help tackle the crisis, Waziri said it's crucial for the Biden administration to release $7 billion in Afghan reserve funds that the United States has frozen — and pump it back into Afghanistan.

In talks with the Taliban about these assets, the US "remains focused on finding a way for the funds to benefit the Afghan people, while not benefitting the Taliban," a National Security Council spokesperson told Insider.

Waziri agreed: "There should be a mechanism that the money should not go just to the pockets of the Taliban. It should be used by the Afghan people and there should be accountability."

Beyond that, Waziri called on the Biden administration to further pressure the Taliban to respect human rights and support a peace process, for the sake of the Afghan people. And the US must work to evacuate the thousands of Afghan allies still trapped in the country, she said.

"Stand on your promise," Waziri said of the US government. "You have to support us."

Hopes to return

To distract from the anguish, Waziri has thrown herself into what she knows best: work.

She has spent the past year mostly behind her laptop, researching and writing about Afghanistan, its government, and its politics. An academic paper she's currently writing discusses the Afghan government's failure to implement transitional justice, which she will present at a conference in Germany this October.

"I want to not forget what we have done in the past. I want to be a part of the history of my country. I want to contribute to the history of my country," Waziri told me.

In the coming weeks, Waziri will become a visiting researcher at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. Next spring, she will teach a class there on the role of women in international security sectors. She also wants to make time to study for the bar exam to eventually practice law here.

Waziri's husband, formerly a pediatric surgeon in Kabul, is working as a fellow at a hospital in Washington, DC. Her son just started 10th grade after finishing the last school year among the top in his class. They often see relatives in Maryland, who moved there from Afghanistan five years ago.

But as Waziri rebuilds her life, Afghanistan weighs heavy on her heart.

Now when she cooks, "sometimes I'm burning my hands or I'm breaking the dishes because, I'm just like, my mind is busy with Afghanistan," Waziri said.

Waziri longs for qurooti, the bread pudding served at the café near her Kabul home; those Friday nights lounging in her family's living room, surrounded by her six younger siblings; Turkish breakfast at the restaurant where she first met her husband and he later proposed to her. She yearns to visit the cemetery where her parents and sister lay after she lost them in rapid succession these past two years. Her father and mother died of heart problems, her sister of COVID-19.

Hope keeps Waziri going. She's glued to the news, following each development from Afghanistan. For all the tragedy, she dreams of a future there. Too many of those dreams – building a school for girls in her home province, Paktika, opening an institute in Kabul to support female lawyers – have not yet come true.

"One day, we will be back. We will continue from the place that we fell down," Waziri said. "We will rise again."